Many companies still using Industrial Age management practices struggle with digital transformation. Steep hierarchies, environments of excessive rules and distrust, and a reinforced command-and-control view of people leaves little room for innovation.

Fast-forward to the Participation Age where people want engaging work and to make decisions on their own. Technology, global competition and the workforce's digital dexterity require a different cultural model to get work done. Managers who take on this more progressive view of people and resources are well-equipped to lead agile and adaptive companies.

According to Forrester's recent report Sustain a Digital Culture, the most digitally aware enterprise leaders are realizing that cultural and organizational transformation will dominate their agenda for years to come.

A lot of cultural issues are at the root of many failed business transformations, yet most organizations don't assign explicit responsibility for culture.

To reap the benefits of digital business, leaders must take a culture first approach to business transformation.

Here to help us understand some common challenges and where to start is business advisor Chuck Blakeman, Kintone CEO and work culture champion Osamu Yamada, and digital business transformation expert Dan Morris.

Nicole Jones: Chuck, why does cultural change leadership matter now more than ever?

Chuck Blakeman: It's a great question. Cultural change leadership really matters now more than ever. It's always mattered, but I think for two hundred years what we did in the industrial age was not neutral. It was really great for the stuff. We got incredible stuff out of the industrial age, but it was wrong for people. It dehumanized them, and we want to rehumanize the workforce and give everybody their brains back. The industrial age did just the opposite. It gave us great toys but in terms of the humanity, it's really a pimple on the face of business, so we need some Clearasil to get past it. The Clearasil in mind is great leadership focused on giving everybody their brains back and learning that if we take care of the people, there's so much new research on this, that when we take care of the people, they take care of the businesses, the clients, and the processes.

Culture is one of those fuzzy things that doesn't need to be so fuzzy, and I think it's time to give it its rightful place in developing an organizational structure. I would also mention that Deloitte University did, to support your statistics, Deloitte University did a bit of research and found that ninety-two percent of the companies they surveyed want to change their organizational structure this year. They just don't know how to do it. Culture, I think, is a big piece of that.

Nicole Jones: What are you seeing happening at a lot of traditional companies and why change now?

Chuck Blakeman: Because ninety-five percent of them are still stuck in the industrial age. We think the industrial age is over in the 70s. The production area has moved on from smokestacks and assembly lines to things like clean rooms and nanotechnology, but the front office looks pretty the same way it did in 1910 with guys in ties making decisions for everybody else. The command and control, top-down hierarchy imposing tasks instead of delegating responsibilities, and worst of all managing people. It's an industrial age concept, managing people. People don't need to be managed. They need to be led, and these are two very different things. Stuff needs to be managed, and in the industrial age people became stuff. They became extensions of machines.

Stuff is truly stupid and lazy but people aren't, so we need to move on from that. The state of most current organizations is they're still treating people like stuff. That's where the emerging work world has to come into change this, and the good news is there's hundreds of large companies and really thousands of smaller ones that are leading the way out of all this, and the data is all on the side of giving people their brains back and changing the way we organize.

Nicole Jones: Excellent. I think Cybozu really aligned with a lot of what you were saying, so I want to ask Osamu what led Cybozu to change its company culture in the last decade?

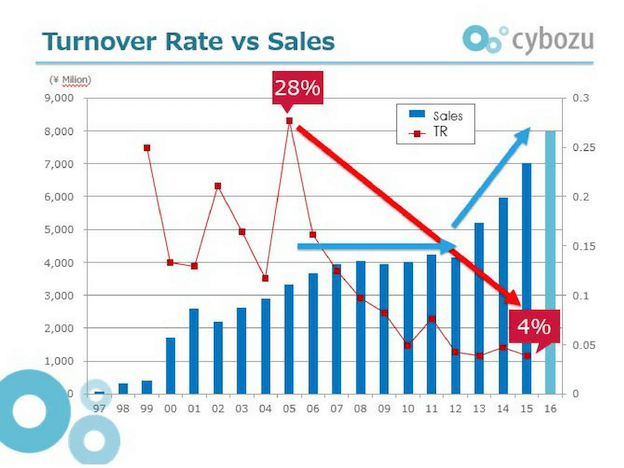

Osamu Yamada: We created a human resources system with a hundred types of work styles for hundred people, because each individual is unique. A one size fits all HR approach does not work anymore. Companies need to adapt to today's global and the digital business environment and that means adapting to their employee's unique needs. If not then face the consequences. We did eleven years ago when employee turnover rate at Cybozu reached into 28 percent. That means that two or three members got out from our company every single month. We had a lot of farewell parties.

We had to start asking who we wanted to be and what kind of company we are. Was putting all of our resources into becoming the biggest company in the market or in the world really worth it, and would that thinking help us in the long run? We were feeling the impacts of losing a lot of great employees that we trust and enjoy working with. Our goal to grow faster and faster as a company so people were working so hard and that was a tragedy. We knew we had to make a big change and we did it. After a few years of restructuring we managed to bring the turnover rate down to four percent.

Nicole Jones: That's a pretty big change. What does Cybozu leadership do to get to that point?

Osamu Yamada: We decided to focus on our employees and researching what we could do make them happier. We started with a leave system that guaranteed jobs for six years, not just for parents taking care of their kids, but for employees needing to nurture their careers outside of Cybozu. We also created highly flexible working hours, and generous amounts of remote work. We quickly realized that it's not beneficial to require everyone to show up at the same time at the same place. This one size fits all approach is not good for employees. It's beneficial for a manager to manage employees, to manage the organization easier. It's more important that people fit in our culture and truly feel like we are aligned on mission and goals to build great things.

It requires our focus on the employee, and working with each person's unique needs. That's why we created the concept of hundred work styles for hundred people focused on what they need to happy, and help them do their best work.

Nicole Jones: What kind of results did Cybozu see after implementing these new HR policies?

Osamu Yamada: We noticed a sharp increase in employee motivation and productivity, but it took a couple years. If you look at the chart you'll see what happened. At first turnover rate was lowering, but sales stayed the same. After six years we introduced cloud services which included Kintone, and our sales took off. It probably wouldn't have grown so fast grown so fast if it wasn't for focusing on turnover rates and building a strong work culture years earlier. I wouldn't say there is a strong relation between turnover rate and the economic growth, but it happened to us. That is the reality. Our mission also changed. We're now focused on making teamwork better around the world, and that, of course, includes our own team as well.

We don't think it is very important to be the capital market winner, but we cannot be the loser, otherwise we cannot fulfill our mission of providing excellent teamwork. Make teamwork better, and as a result we make society better. We want to do good things in the world, not just to raise our market cap.

Nicole Jones: Thanks Osamu. Chuck, I know Crankset Group has a lot of really progressive, interesting approaches to creating a flexible work culture. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Chuck Blakeman: My perspective is really you don't build a culture. You simply live out what you believe, and that's how we built Crankset Group. It's sort of a chicken and an egg thing. Let's say the chicken came first. The chicken is our beliefs. What do we believe, determines everything that we become, and our culture is a direct relationship to that. We have some basic fundamental things we believe about, for instance, why business exists. Is business war or is business, do you exist to contribute? Why our particular business exists, to add value or to destroy the competition? Why leadership exists. Does leadership exist to serve or does it exist to command and control?

Then things like why people come to work. Do they come to work to make money or to make meaning? What defines success? Is success from just profit alone or is it profit with contribution and maybe one of our biggest ones, one of our biggest belief systems is we believe people are smart and motivated, and the industrial age assumed that people were, Frederick Taylor in 1911 wrote a paper called Scientific Management, and in that paper he defined the employee as stupid and lazy. "The average employee is so stupid they more resemble the ox than any other type of," is the quote from the book. We don't believe that. We believe people are for the most part smart and motivated. We built our culture around the assumptions that our business exists to contribute, that people come to work to make meaning, and that they are smart and motivated.

When we have that belief system, that's the way we make decisions, and it's sort of a descending train, if you will. If we believe this, then we think this, and if we think that then we decide this way. When we decide that way, we decide that way often enough, that becomes our habits and that becomes our culture, and that becomes our destiny. All of that cultural stuff comes from what I believe and what the leadership of this company believes. That's the core of everything that we have to do culturally, what do we believe.

Nicole Jones: It sounds very conceptual, and like you said, like kind of chicken and egging problem there, but still it remains very hard for companies to morph into a flexible work culture. Why is it so hard for companies to create or morph into flexible work cultures?

Chuck Blakeman: The clever answer is it's actually not. It's really incredibly easy to change the culture. All you have to do is change out the leadership and get somebody in who believes the right things about the business. That's the hard part. If you have leadership in place who does not understand the value and hasn't yet seen how much more productive, how much more revenue, profitability, productivity, lower turnover. If they haven't seen all this stuff then it's very difficult for them to see the value of changing their culture. It's working well enough right now, and leave it alone because what we're going to do might be worse. It's really very easy to change the culture, but only if the leadership believes that and that's the key.

The leadership tends not to believe that people are as smart and motivated as I am, and all the other things that come with that. There's a trust factor that they haven't yet seen. When they set people free, they rehumanize the workplace, give everybody their brains back, it scares them to death because they think of that as chaos and anarchy, and all the other things that might come from that image, when, in fact, the self managed companies that I'm aware of, the hundreds of large ones and thousands of small ones, they're more organized, they have better processes. They have exponentially lower turnover as Osamu was mentioning. All the data is on the side, but the emotion is on the side of let's keep things the way they are, and there's just a lack of experience.

As more companies do this, and more companies show the data, it'll be easier for other companies to get onboard, but it's a belief system issue.

Nicole Jones: Thank you. Dan, we're going to get to you in just a moment here, but I wanted to get Osamu, your thoughts on this, and why it's so hard to morph into a flexible work culture.

Osamu Yamada: I totally agree with Chuck. In Japan, so flexible work style and work-life balance is still not widely accepted. Traditional corporate culture in Japan prefers employees works extra hours. It's placing a lot of stress on families, especially working mothers who often must decide between their career and staying home to raise children. It shouldn't have to be this way. It's a large reason why at Cybozu and Kintone we encourage remote work and the flexible work hours. Still many companies view this as losing control of their employees.

A lot of traditional corporate cultures are based on mistrust. Letting employees decide when and where to work is based on trust and transparency between employee and the employer. A lot of companies don't have this, and perhaps a company that isn't doing bad in the market does not feel they need to change, so they keep doing business as usual. With all the change in the global business market, they cannot think like that forever. Many companies are already thinking ahead by creating a flexible and agile company culture built on trust.

Nicole Jones: And Dan, can you tell us why does digitalization demand this agile culture that both Chuck and Osamu were talking about and how does cultural transformation lead to the adoption of technology.

Dan Morris: First of all when we start to look at digital transformation and we roll it on up from the tactical levels which say I'm going to buy a tool or I'm going to replace an application, and that's part of digital transformation. When you start to roll it up and you start to look at the fact that it is both invasive and pervasive in companies, everything is changing. That means all of the technology is going to within the next five to ten years change out. It also means that the company is going to be a very different company, and part of this is as a direct result of where the technology is going globally and how it's creating a new type of global technoculture where people in all walks of life and in all levels in companies have access to very sophisticated technology and mobile devices and have access to very sophisticated types of applications and different types of social media and social applications.

We've now reached a point where people are no longer afraid of technology, but the technology outside of companies has outpaced the technology inside of companies, so that people now have access in their personal lives to much greater flexibility and much more capability with the technology they have than they're able to find within their companies. That is a cultural change that's now coming back into the companies from outside. In the past certainly pre-1990 we found that people were absolutely afraid of the technology, because they didn't have access to it. The internet really changed everything and then mobility computing changed everything again.

That type of change in the broader cultural sense is now being brought, as I said, back into the companies and starting to change the way that everybody looks at technology from an expectation perspective. That expectation perspective is now starting to filter back into organizations, and starting to drive another level of change within the companies themselves. A lot of people start to look at that as digital transformation. While that's part of it, it's certainly not where it needs to go, because we're now becoming at risk of creating the same type of environment that we had before that led us to extreme complexity within the companies, hard to change applications, a lack of agility in our ability within companies to change.

From the outside it's now being driven in. We're starting to see that now start to filter up into management. I had one of my clients, just very briefly, say that they're having a difficult time in hiring people because the technology, a lot of it was still this old green screen technology. They said people just don't want to do it. We're seeing that start to have a real impact on companies on the technology they use, on the way they're starting to move out of older systems and into newer systems.

Nicole Jones: Thank you, Dan. This next question for Chuck. This is definitely building on Dan's response but how is the digital world driving innovative company culture?

Chuck Blakeman: That's a great question. The whole concept of self-management and giving people their brains back and treating people like adults at work, it's not a new thing. There were people, Mary Follett and others, in the early 1900s talking about it. Bill Gore built his entire company. The company that makes Gore-Tex around it. They have ten thousand people. In the 1950s he started that company in his basement with his wife and there was a big movement in the late 80s, early 90s toward self directed teams, and that failed for two reasons. One was because the management actually never changed the organizational structure to support true self management. It was very hypocritical. We want you to pretend to be self managed but we're still going to manage you.

I think the bigger reason that it failed, it gets to this point that Dan is talking about, is that the technology is there today in ways that it never was. People were afraid of it before, and it's there in ways today to support this kind of disparate way of working from homes and flexible hours and those kind of things that was never available in the past, and I'm convinced that the reason that the participation age is racing forward and an emerging work world is happening the way it is is because companies are embracing this.

I could just give you scores of examples of companies that have built their whole organizational structure around the belief that people are smart and motivated, they can trust them, they can have flexible hours, all of this kind of stuff, and then backfill that with technology that has allowed them to continue to build relationships even when they're absent from one another. It's absolutely key to the future of this. I think it's central to the future of the way we're going to work is how we develop the technologies to support that.

Nicole Jones: Excellent. Thank you Chuck. This next question is for Osamu, and we are going to transition a little bit more into how to become a cultural change agent. The question is where does cultural change start within the organization? Is it the top-down C-suite application or it the more bottom-up from employees?

Osamu Yamada: Actually both I think. Line of business managers know the strengths and weaknesses of their departments better than anybody else, there is no doubt. We have to get ideas and information from them. Leaders should use this information to consider which one is best. Maybe the leader's opinion is best, but maybe not. Leaders have to see all the information to make good decision, but it's up to employees to voice opinions and share concerns. It's up to leaders to create a culture that supports this kind of transparency and feedback, so whether it's top-down or bottom-up management, it doesn't matter which one.

It's integration. We gather the opinion from the bottom, discuss together, then the leader makes a decision and we move from top to bottom. We use groupware like Kintone to encourage this collaboration, to share knowledge and to create transparency.

Nicole Jones: Excellent. Thank you, and, Dan, how do you convince people in your organization or your clients I should say, that change is necessary?

Dan Morris: The simple answer is you have to convince them it's to their advantage to do so. As long as someone believes that the status quo is to their advantage, they're not going to change or they will resist change. In selling change, which it really is in my opinion a sales activity, you really have to define why things are going to be better, how they're going to be better, and how it's going to help both the individual as well as the company to succeed better. I think that a lot of the things that have happened in the past with change, especially with IT, have from a use standpoint have been poorly introduced. People have been poorly trained, and there is a great deal of fear with the introduction of new technologies.

Not fear from the use of the technology. People aren't afraid to touch the technology and to use it, but afraid that they won't be immediately successful, and in a lot of companies today there's, although they talk about innovation and they talk about change and a lot of things, they really aren't organized or set up to support that. That's the type of fear that's being introduced. Where you can start to work with management, work with IT, work with the people on the floor and start to find ways to drive out that fear, to look at the way that that organization through the introductions of new technologies, new management approaches are going to allow people more freedom, but at the same point in time not have responsibility without the authority that should go along with that responsibility.

You add the authority to do things in there. You add the way that people are now going to be evaluated in their performance evaluations and those types of changes then are really part of the foundation of moving into any type of a digital transformation activity. Without that foundation, it's tough to think that they're going to succeed.

Nicole Jones: Well put, Dan. Chuck, what's your take on this? How do you convince people in an organization that change is necessary or it's not scary? It's something to be embraced, or maybe that's not even the right way of going about it.

Chuck Blakeman: Yeah. I don't try to convince people because I think the better thing to do is first, Dan alluded to it, number one is data. The joy in this is all the day is on the side of building organizations differently. I was having a Twitter conversation with Tom Peters and he said, "I never want to fly on an airplane that is created by self-managed companies. Make sure they are labeled." That's an emotional response. That's an emotional response. My data response was, "Well, the GE aviation division is self managed. There are no managers in the GE aviation division, and they make most of the airplane's engines in the world, so you're going to have to take the bus from now on."

You go with the data first, and Osamu, I mean beautiful intro. He went from twenty-eight percent to something like four percent turnover. That is astronomical cost savings. Ricardo Semler took his organization from thirty-five percent turnover to two percent. Wegmans Groceries in an industry where thirty-eight percent is the norm, they are at three percent turnover. You just look at companies that are moving forward: better technology, better communications and a whole new way of leading rather than managing, and you find the most productive, best, most stable companies in the world. Number one is data.

Then number two is why, and that's what I'll do with people who don't understand this stuff, is I'll ask them why they're doing what they're doing. A friend of mine calls it the management tax. Look at the management tax in organizations. One out of seven or one out of ten people has to be a manager, and if you put people in self managed teams you eliminate that entire tax. That's an astronomical cost there. We always start every conversation with why, and that's what helps us work with other companies. Rather than saying you need to change the way you're doing things, we would want to approach that with here's why, and data is part of the why.

Some people will come in the altruistic door. They want a better legacy. They want to know they treated people better. Others will need to see the hard data, but you have to have a great why, and if you don't see the importance of why then you won't see the importance of changing. To articulate a great why first and then people will want to jump onboard that.

Nicole Jones: We have a lot of people tuning in today who are definitely agents of change, who are in leadership roles and are personally involved in driving change. Let's move onto how do we create this cultural change roadmap, a little bit more into the tactical approach and how we create that vision. We ask the great why, but then let's go into the plan of how do we create the best way for clearly communicating change and new ways of working together? How do we demonstrate that and this question is for either Dan or Chuck if you'd like to answer that?

Dan Morris: What I've found is the first thing we have to do is figure out what the end objective is, and the panel all alluded to it earlier in kind of defining the type of company and type of environment. Aside from the type of company and the type of environment, which I believe can be a little bit different in different types of industries, when you start to talk about especially digital transformation, you have to define what that is, that box is going to look like, and then once you have an understanding of the capabilities that are going to be available, why you want to do that, you can now start to ask how do we do that.

When you start looking at the how do we do that, one of the big components turns out to be people, because people will make something work or make it fail. You need to at that point align the change that you're trying to elicit in people to the timing and to the differences that you're going to see in the evolution of the company as it moves from where it is today in mainly an interfaced IT world, to a flexible, integrated world that in my opinion is going to be based largely on BPMS technologies in the future. The type of technologies we find though, like a BPMS technology versus a more traditional technology, will also have a profound impact on the way people have to change and what they have to do.

As an example in a BPMs type technology base, people are expected to do models. They're expected to understand what those models mean as far as how they're operations work, and then to design how things are going to change. That's where innovation comes in with iteration and those types of things. The type of environment that you're going to ultimately try to create will help you define what that culture has to be. At this point I'll turn it over to Chuck to agree, disagree or carry forward.

Chuck Blakeman: I appreciate that. I would agree. I'll take it a little different direction to add to it because I think you've covered all that well. When we ask, when we get with a company and help them figure out where they want to go, I think, Dan, you mentioned they have to figure the big picture out; what is the objective that they have in mind? Before they do that we like them to figuring out what they're really good at, because that can actually it'll either guide where they end up, or if they don't like what they're really good at, it'll cause them to hit some change buttons. There's four very simple questions we have for companies when asking them to create a vision for where they want to go.

Number one is what are we really good at right now? What are really good at, and include the bad things that you're good at. We're good at high turnover. We're good at low productivity. Focus on the good stuff as well, and make a list of all that and codify it down to the few things that you really think you're best at, and then the second question is why. Why are we so good at those things? That's when you begin to uncover what companies actually believe and that's where their culture lies. People too often ask companies to express their culture in some vision statement when in reality their culture is best expressed by simply looking at who they actually are and what they actually do on a regular daily basis. Why are we so good and doing these things?

Then question number three is do we like being good at these things or do we want to be good at something else? If we don't like it, we have to change, and then the fourth one really isn't a question. It's an application. If we want a different result, we need to believe something different. We need to identify the right beliefs to get the right results, and really this is why consulting doesn't work in so many cases, because we go into change, to engineer a result by changing out an assembly line or putting in a digital product or something like that, and nothing really changes.

I think, Dan, somewhere in your writing, correct me if I'm wrong, but I thought I saw it's not about digital transformation. It's not about bringing in a new piece of software by itself. It's about software supporting a culture and supporting a way of doing business and the digital transformation is a piece of that ,and that's where it breaks down as we go in and try and put in new software like we put in new assembly lines, and nothing runs differently because we didn't really fix the cultural issues first. I'd start with that.

Nicole Jones: This next question is for Dan, and it's about designing our culture then. As work culture, digital transformation, we're seeing this connection and also a lot of IT decisions, technology buying decisions are leaving the IT department as we talked about. Our world is just being disrupted by new digital and technology tools and line of business managers are feeling more empowered to seek out their own solutions. Dan, I want to ask you who should be leading this effort? Should it come from IT or should it be more operations led, or maybe both?

Dan Morris: It needs to be collaborative first of all. Second of all I think that those companies that allow the different divisions to just go off on their own are going to find themselves in a world of pain. That's not to say that IT has to be responsible for everything, but in what I'm proposing is one of the initial steps in digital transformation is to figure out the architecture of the future. In the past all the new applications, all the new technology, it's just kind of been shoved together and interfaced, and what we've created is an unbelievable complexity. It's a complexity that we almost can't deal with. We need to avoid that in the future, so we need a set architecture and that's a technology architecture and it needs to deal with first of all the hardware and the middleware, and the operating systems and all that type of thing to make sure that it all fits together.

Then within that context we need standards. Once we have those standards in place to make sure that everything that we buy, build, whatever will fit together in an integrated manner, we can now then allow other organizations within the company outside of IT to take the steps that they're starting to take now, but if that's not better under control right away, we're just going to recreate all the problems that we have today, and our digital transformation is going to fail.

Nicole Jones: Collaboration is a big piece.

Dan Morris: It is, and the responsibility for it I think can shift over time, but it needs to, right now as an initial step, be centralized within IT, and then once those standards are built we have that organization, that framework, that architecture that we're moving towards. At that point, just so things fit into that architecture the right way, is really all that's going to be necessary. Whichever approach you take and however you do that, it's going to have a direct cultural implication because as things first of all move to more collaboration between IT and business, which today there is still chasms all over the place, but as those start to become more collaborative and become closer together, the methods become more integrated between business methodologies and IT methodologies, the culture and the way that the worker and the manager interact with IT, and the way that IT becomes embedded, it's going to cause a tremendous knowledge shift and culture shift in the way that these people have to work together.

Nicole Jones: In the best way possible, we have gone to great lengths or have been really invested in nurturing a culture. What can we do to protect it? What can we do to ensure there is lasting change, if there is even such a thing? I'll start with Osamu for answering this question.

Osamu Yamada: I think by not focusing on being the market winners, but instead focusing on the employee and creating teamwork, it creates the dedication we need for our companies to be successful and thrive in a changing landscape. I think we've been doing a great job. I don't think we are successful yet, but so far our culture has been working. We are still too small to make a impact to the society. We are still far from being the greatest team or company in the world. It's challenging we kind of need to pursue, so there's is no doubt.

Nicole Jones: Thank you Osamu. Chuck, maybe I'll let you go ahead and step up for this.

Chuck Blakeman: Yeah. I think we have this phrase, "Only the paranoid survive." What we mean by that is that we don't want to rest on our laurels. We don't want to think we have ever arrived. I like Osamu's view of not being the best yet, not being great yet. We're never far enough along, and so that's a part of our culture. We're always thinking about how we can continue to improve, and in that context change really does become our constant. I know that's a trite saying, but Apple destroyed all its great products along the road because they knew if they didn't destroy those products somebody else would, and I think that's a great way to continue to make sure that you keep a good culture, is that you continue to be willing to change with everything new that comes along.

Then probably on a more practical basis, we get everyone involved in designing the changes around motivating why's and making sure that there's a buy-in and an ownership by everyone on how to change and why to change. On a macro level I think the one thing that will keep this going in the right direction is the data itself. The data on transforming cultures and organizations in the direction of an emerging work world is just too compelling, and eventually it's going to win out on its own, but in the meantime be paranoid and expect that change is the constant, and be willing, and not just be willing but embrace it on a regular basis.

Nicole Jones: Thank you. Dan, if you can please give us your perspective on what we can do to create a lasting change.

Dan Morris: We have to get back to, and we've lost it, but we have to get back to where people trust their companies, where they trust management, where they care. With the downsizing that's gone on, with everything that's happened in the last fifteen years, there's been a great deal of eroding as far as loyalty is concerned. People jump jobs for any reason constantly. I think that part of that is there's a lack of trust between management and the staff. There is an animosity in a lot of companies between the business operation, production, and in IT.

We have to collaborate and we have to work together to break down those barriers, because only when we can do that and we can start to have truly collaborative teams that trust one another and have the performance information to allow them to iterate and to look at change creatively, until we have that trust, we're going to have problems with both business transformation as well as digital transformation. That's where I would start is to build that relationship, to build that trust between management and staff.

Nicole Jones: Excellent. Thank you all very much for your thoughtful contribution to this conversation.

About the Author

Nicole is Director of Marketing at Kintone, with 10+ years experience in content strategy, campaign management, lead acquisition and building positive work cultures of empowered, purpose-driven team members. She spent seven years as a journalist, previously serving as a CBS San Francisco digital producer, NPR contributor, Patagon Journal deputy editor and reporter for several publications, including the Chicago Tribune. She's passionate about the tech for good space, social entrepreneurship and women leadership. On the weekends, you’ll likely find her putting her Master Gardener skills to use in at community gardens in Oakland.