In his 1986 book, Finite and Infinite Games, published scholar and former Director of Religious Studies for NYU James Carse argued that all engagements are either “finite” or “infinite” in nature. At their most basic, “a finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.”

A finite game “must come to a definitive end.” According to Carse, “it will come to an end when someone has won...when all the players have agreed among them who is the winner.”

War is often an example of a finite game; if one reviews World War II, for example, there are clearly defined players: the Axis Powers and Allied Powers. The “game” has a beginning and end and a mutually-agreed upon winner.

But what about infinite games? How can a game with players be about “continuing the play” rather than singling out the superior player(s)? “Infinite players cannot say when their game began, nor do they care...the only purpose of the game is to prevent it from coming to an end…”

Art is probably the clearest example of an infinite game. There is no “beginning” or “end” to the arts, and while there may be conflict between the players themselves (Carvaggio v. Giovanni, Banksy v. King Robbo), the goal is never to bring the exploration of art to a close.

(In the case of Italian painters Carvaggio and Giovanni, the latter expressed their feud by using his rival's features for the image of the Devil in his work, The Divine Eros Defeats the Earthly Eros, displayed left.)

(In the case of Italian painters Carvaggio and Giovanni, the latter expressed their feud by using his rival's features for the image of the Devil in his work, The Divine Eros Defeats the Earthly Eros, displayed left.)

What then, do these gameplays have to do with workplace culture and conflict? It’s about shifting our view of workplace conflict from that of a “finite” game to that of an “infinite game.”

Company Culture Is A Game, But What Kind?

When we find ourselves in conflict with our coworker, we are quick to view the conflict as a finite game: there are two (or perhaps more) players, and there must be a winner between us. Someone’s vision or views will come out on top. HR policies often adopt a similar stance: identify the players in a problem, punish/reward the players accordingly, and then archive the incident away in a file cabinet while the business remains the “winner-takes-all.”

But treating conflict from a “containment” perspective overlooks the key point: that these clashes—and how we resolve them—don’t have to be seen as hiccups in an otherwise good culture but rather as opportunities for a better one. In other words, how we handle conflict is an opportunity to improve culture rather than just a way to contain problems.

The “infinite game” here is company culture. Like art, it should have no end. And every player in it can help contribute to its improvement--even when things aren’t going well. So how do we re-structure conflicts to help progress company culture? By shifting the way we tackle conflict when it occurs.

Types of Workplace Conflict & the Culture Problems They Create

Workplace conflicts usually play out a few ways:

1. If HR isn’t involved, members vent/gossip to others to create alliances/support to “win” the conflict. Perhaps you know it’s in the company’s handbook policy to pay for commuter passes to the office, but management has always dismissed your requests. So you talk to others on your team and rally support until enough members confront management with you.

2. If HR is involved, you receive notices of private, closed-door meetings where you and the person you’re in conflict with are expected to “talk it out” or give each side of the incident until HR feels they have enough evidence to make a decision.

These two kinds of situations rely on a lack of transparency to handle the conflict. One uses hidden communication channels to build momentum out of sight, the other relies on keeping a conflict hush-hush until the company (via HR) has made a final judgement call.

The problem with this lack of transparency is that it doesn’t just hurt the company’s chance to use conflict as a way to improve culture, it actually fosters a culture of distrust between team members, leaders, and departments. So if transparency is the first problem in how we handle conflict, how can a company tackle that without turning themselves into a hotbed of drama?

By creating transparent channels for conflict management that allow individuals to express their concerns/hurts WITHOUT shutting down the opportunity to resolve those problems in a fair and reasonable fashion. Essentially, people get to talk about what’s wrong but that doesn’t mean talking is a substitute for resolving the problem.

Sounds difficult to achieve? It doesn’t have to be.

How To Promote A Better Culture Through Conflict With The Aspiration Engine

There’s a new kind of transparent conflict management tool available: the Aspiration Engine. And it’s designed to give companies a safe structure in which to begin exploring—and resolving—conflict.

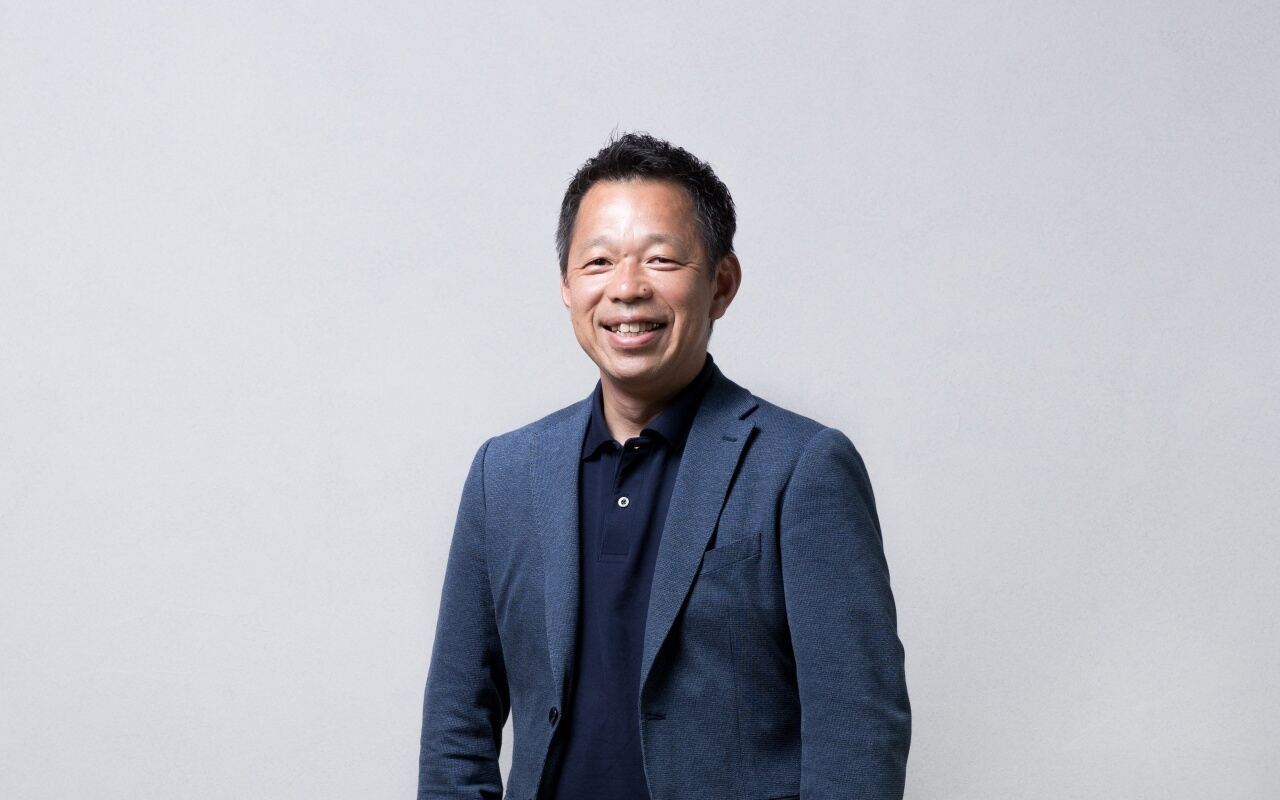

Developed by Kintone’s parent company, Cybozu, Inc., to help combat their terrible company culture during their formative years (at one point they had a 28% year-over-year turnover rate), the Aspiration Engine has become an integral tool to both Kintone and Cybozu’s progressive-even-by-Silicon-Valley-standards workplace policies.

"Before things changed, we were hosting goodbye parties every other week for people leaving. It was crazy," recalls Former Chief Director of Human Resources and current Vice President at Cybozu, Osamu Yamada.

Since employing the Aspiration Engine, along with other new resources for employees, Cybozu’s turnover rate fell to four percent and earned a reputation as one of the best places to work in Japan.

Here’s how the Aspiration Engine works:

1. Individuals can submit problems they’re experiencing (anything from commuter passes not being available to a lack of clear strategy from their department heads). BUT as part of submitting their problem, they must also identify what an “ideal” outcome would look like. If the problem they see is resolved, what would their work experience be?

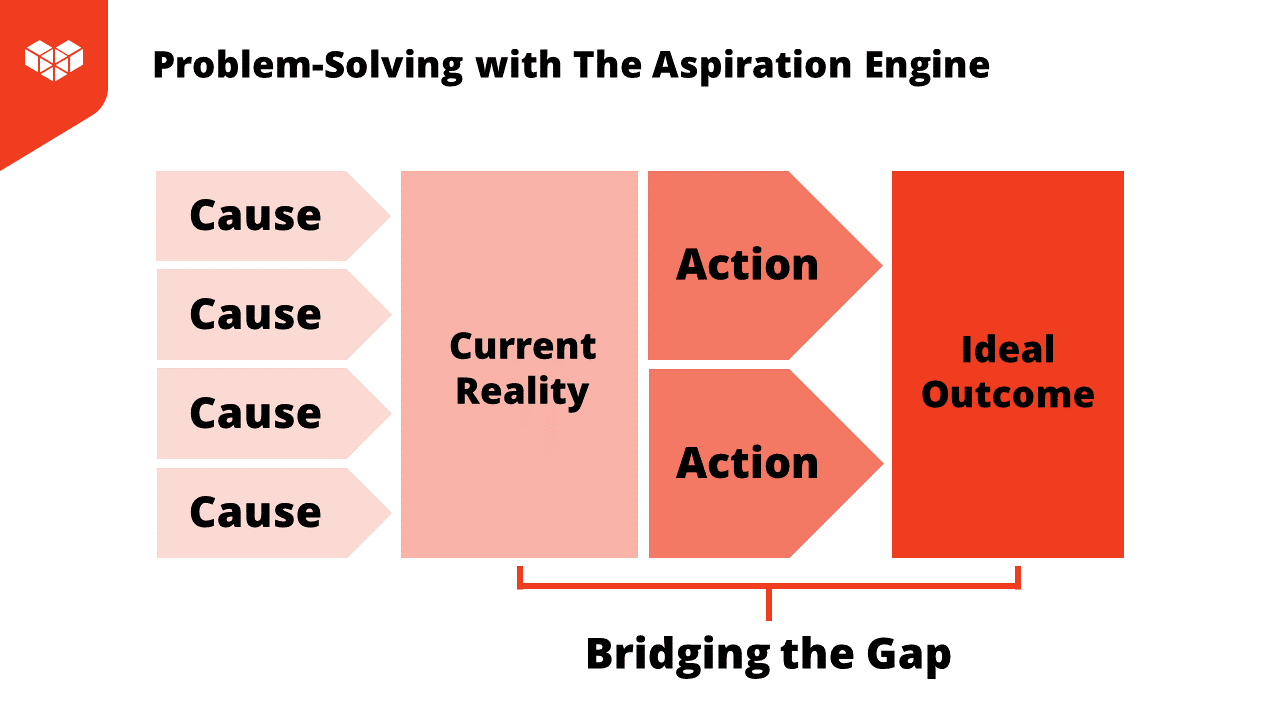

The Aspiration Engine focuses on bridging the gap between the current reality employees experience and the ideal outcome they want to see. The Aspiration Engine is designed to not just give employees a productive way to identify and resolve their issues but also a chance to improve relationships with others through open dialogue.

2. Once submitted, the problem is introduced to the relevant players (perhaps the team or maybe several teams depending on the nature of the issue). There’s a chance for others to discuss their own experiences related to the problem (if others are also unhappy about a lack of commuter passes, this is the chance to bring their feelings up). It’s worth noting that sometimes during this discussion there are conflicting views on the ideal outcome—not to worry. This is an expected part of the process, as people have different expectations of how things should work. One of the core features of the Aspiration Engine is helping clearly distinguish and identify different goals/needs and explore which ones are achievable.

This transparency in step two does several things: it gives teams a chance to relate or connect their frustrations, it builds trust between members by giving them a safe environment in which to explain their hurts to one another, and it gives management a chance to “clear the air” and stay in touch with the problems their teams face. Rather than driving these conversations to back channels, it brings them into the light.

3. Once the issue is fully identified (sometimes step two will show that other members of the team have similar but different grievances), each issue is assigned to teams of six to eight individuals (does not need to be sorted by department or by how personal the issue is) who must then work out what actions the team or company needs to take to shift the current reality into an ideal outcome.

Part of steps one through three involve also identifying the causes for the perceived problem. This is done in a way where causes are not an opportunity for blame but a chance to honestly identify what’s getting in the way of resolving an issue (in our commuter pass example, two “causes” might be management not having reviewed the handbook recently or an overloaded admin team failing to follow through on setting the process up).

4. Once the teams are done working, they present the actions needed to resolve the issue; these actions are assigned and timelines are set to ensure follow through occurs and the issue is resolved.

In Summary

By opening conflict up and creating a formal process for it, the Aspiration Engine allows for conflict to become an opportunity for trust, transparency, and an overall more open company culture. Conflicts are no longer bumps in the road but a chance to build on what goodwill already exists in the company.

In the end, the infinite game of company culture continues on. Only now it’s a better, more enlightened version of what it once was. No winners, no losers, only mutual advancement for all involved.

How to Use the Aspiration Engine Yourself

To learn more about the Aspiration Engine, watch Kintone free webinar recording: How to Improve Team Culture With Collaborative Problem-Solving. This webinar explores in depth how Kintone’s own team uses the Aspiration Engine to tackle and resolve its own issues, with great success.

You'll learn:

- How to use the Aspiration Engine methodology to resolve challenges (even when remote)

- How the Aspiration Engine helps foster a space for people to openly communicate with their team

- How to encourage individuals to take responsibility and raise issues as they occur for a more open, transparent workplace environment

About the Author

Michelle is the Content Marketing Specialist at Kintone. She is a content marketing expert with several years in content marketing. She moved to San Francisco in 2015 and has experience working in small businesses, non-profits, and video production firms. She graduated in 2012 with a dual degree in Film and English.